Quaintance is a very impressive book: at almost 30×40 cm (about 11.5×15 in.), its 168 thick pages are full of beautiful reproductions of art by one of the most idiosyncratic gay artist of the XXth century. It was published in late 2010 by Taschen, but since it was rather expensive, I waited some time to buy a copy. Now you can find it at almost half price1 and it’s worth every penny (cent? centime?), as I’m going to try and show.

Like all good monographs, it begins with a short but informative biography by Reed Massengill of the artist George Quaintance (1902-1957), an American painter who first did some vaudeville dancing, before launching a commercial art career in New York City, doing everything including hair design. His male illustration career began in the 40s with works for body-building magazines, and his moving to the West Coast in 1947 (because his lover wanted a warmer climate) led to his involvement in the Physique magazines, the precursors of the gay press, and specifically with Bob Mizer’s Physique Pictorial, probably the most famous, but hardly the only magazine of that type (that’s where Tom of Finland was first seen in the USA, long before he began drawing inflated male dolls).

I first encountered Quaintance’s art in books about this period (including the excellent Beefcake book, which sported one of his paintings as a cover) and immediately thought that this artist brought something to the table that others didn’t: there were a lot of gay art published in that period, but most was by more or less gifted amateurs, while someone like Quaintance had that certain quality that went beyond the ability to faithfully represent the male body.

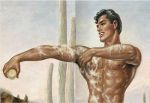

Readers of that period obviously appreciated Quaintance’s work, which regularly appeared in Physique Pictorial and other beefcake magazines right until his death from a heart disease at age 55. Throughout the 50s, he had his paintings reproduced in cards or prints, earning a good living that must have been very satisfying for a man who seemed to have been openly gay from early in his life (or as openly as he could in that period). His work was forgotten in the following decades, but it was rediscovered in the 80s and 90s, leading to a first book in 1990 by Janssen Verlag, unfortunately all in black and white. This new book might be far more expensive, but it’s also the first time Quaintance’s art has been reproduced so beautifully. Case in point: the first pages of the book, showing excerpts of paintings at such a size that you savor every brush stroke, every bump on the canvas, as you can see below (of course, it’s even more impressive in the book).

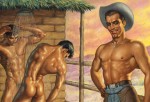

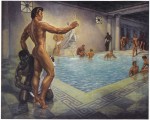

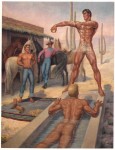

If in his early male art paintings Quaintance chose (or had to) conform to the reality of a particular model (such as on the covers of body-building magazines above) , his beefcake work shows his inner world taking over, in the themes and settings he chose as well as the way he represented the male body. The themes were often shared with other gay artists of that period, with a lot of cowboy scenes. There are also more original settings, such as the two ancient Aztec paintings, Roman and Spartan baths or the famous one with Egyptian slaves building a pyramid, where the almost-naked men are shown from behind, all muscles tensing, glistening under the sun.

The historical paintings might be decidedly kitsch and have nothing common with realistic historical imagery, but they’re opportunities to show an all-male society where nudity is socially acceptable (well, acceptable for the 1950s). A lot of gay artists of that period looked for such excuses to circumvent the drastic censorship—so don’t expect explicit sex or even an erect cock here, but at the same time, they’re part of a mental landscape populated only by manly guys, a landscape that was appropriated by gay artists and their admirers.

The cowboy setting might look like the perfect one regarding the fact that it’s historically-inspired, more or less male-only and it provides yet more opportunities to show naked or near-naked men. Moreover, the mystique of the Far West, already potent in mainstream society, brings to life a gay utopia, where Whitmanesque comrades share spartan accommodation, when it’s not simply the banks of a natural lake.

Homosocial milieus were nothing new in the 50s, of course, but maybe for the first time since the fall of the Berlin gay scene, gay men were beginning to build an environment they could call their own. No wonder they responded so much to Quaintance’s (and other artists’) idealized views of the past.

Idealization also occurred in the way Quaintance used real-life models to create his Frankenstein monsters, taking a head here, a torso there, to build up his perfect men. Fortunately for him, those monsters tended to spend a lot of time washing themselves and admiring each other.

I must admit I was surprised by the audacity of some of the paintings, not only because a hint of pubic hair was shown here and there, but also because some scenes go far beyond the mere “men together bathing” into “naked men looking interestedly at each other” territory—see the Morning in the Desert painting2. In other words, Quaintance managed to make us feel not like voyeurs, but like participants in a time and place where openly gay desires in public were possible, something that must have felt like a crazy dream in the 50s (it sometimes feels the same nowadays, doesn’t it?).

One of the big differences for me between gay art from that period and its more contemporary equivalent is the joyfulness of the situations, the innocence of the characters depicted, as if they lived at a time before human beings were separated into “homosexual” and “heterosexual”. The gay male gaze is obvious in the themes and art style (look at those finely painted muscles, round asses and pectorals), but the men portrayed aren’t aware of it, they just are handsome and desirable.

Quaintance created 55 beefcake paintings, of which 18 originals are lost. In this book, all the original paintings still known are reproduced full page, and the whole lot is shown in smaller size, with comments for each one. One hopes that a more detailed biography of George Quaintance will someday be published, but until then, the short one included here and the comments on the paintings will have to be enough. Readers will probably spend more time poring over the art anyway, thanks to the efforts of the publisher to offer us a quality of reproduction that Quaintance definitely deserved.

Notes:

- You can find this book at the original price from its Taschen, its publisher, or for far less somewhere else, for example at Amazon

. ↩

- Even with “realistic” pretexts, alterations sometimes were required: look at this entry from a recommended website dedicated to Quaintance art, which explains the changes that had to be made to the painting below so that it could be used as a cover of Physique Pictorial. No more looking at another guy’s crotch. ↩

Bluesky feed

Bluesky feed