Teleny is the Great Enigma of gay pornography. Nobody’s sure who’s written it, the multiple editions contradict each other, and the most famous gay man of the 19th century might be involved in what remains for gay people the most famous piece of erotic fiction ever written.

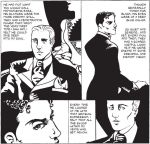

What Jon Macy (whose Fearful Hunter I’ve recently reviewed) has done with his Teleny and Camille graphic novel1 is impressive: adapting a work with such a weighty historical and sensual baggage is no small task, and he’s done so by creating visual narrations suited to the powerful prose, without shrinking from the less palatable aspects of the story, but also by acknowledging that this is a fiction, and more than that, a fantasy that was created in a specific culture for a specific audience.

But let’s rewind a bit: the year is 1893, Britain has some very anti-gay laws on the book and Oscar Wilde is two years away from being branded a “somdomite” by his lover’s father, with the well-known consequences that ensued. Leonard Smithers, a bookseller who also played a large role in publishing erotic and Decadent fiction, announces the upcoming publication (in a small, pricey print) of a “thrilling story”, on the subject of “the Urning, or man-loving-man”. This book is Teleny, or The Reverse of The Medal, a highly sexual story of love and loss between two men. Set in France (“perversion” is always set abroad), it was, in fact, a partially rewritten version of a manuscript which, so far, had only circulated among friends of Oscar Wilde, thanks to the go-between efforts of yet another bookseller, Charles Hirsch (this one was French). Hirsch later claimed that Wilde himself had in 1889 brought him the manuscript, originally set in London, so that some of his friends might come to Hirsch’s bookshop, take the book to read it and then bring it back (it was very dangerous to have such literature at home). In the following decades, the uncensored version of Teleny was only available in French, and it was the 1984 edition published by Winston Leyland and his Gay Sunshine Press that brought it to an English audience. But by then, the idea that Wilde might have written some parts of the novel had taken root, though even today, that is bitterly argued. What is sure is that Camille and Teleny’s story is still as unforgettable as it was when it was created.

Camille Des Grieux, a member of the British high society, meets René Teleny at a charity concert where Teleny plays the piano. Something passes between the two men, but nothing happens—nothing physical. But Camille is beset by visions, of exotic and long-ago lands, of Hadrian weeping over Antinous’s body, of Teleny standing naked while Sodom and Gomorrah are razed, “exposing himself to the thunderbolts of heaven and to the flames of hell”. Their relationship will develop by fits and starts, thanks to a common friend, with Camille trying to make sense of feelings new to him, not knowing whether he should avoid Teleny or search him out. The first half of the book leads to their falling into each other’s arms for the first time, culminating in a detailed night of blissful sex.

Without revealing too much to those of you who don’t know the book, I’ll just say that this isn’t a happy ending kind of romance. But there are lots of interesting episodes leading toward the original ending—an ending that might be seen in the light of the doomed romances genre, so prevalent at the time and which has always been enjoyed by the public (Romeo and Juliet, anyone?), and thus can’t, in my opinion, be wholly attributed to societal homophobia.

The fact that a 150-page book could be adapted into a 250-page graphic novel is a testament to the richness of the text, which, as you can read in Jon Macy’s interview, is what attracted him to this project. That richness certainly provided the artist with an evocative material which he both transcribed in pictures and elaborated upon, making the reading of his graphic novel an immersive experience.

For example, one of the early meetings between Camille and Teleny is in a greenhouse, full of flowers grown in an artificial environment. What more Decadent setting could you imagine? Macy makes full use of this, drawing the luxurious vegetation as well as using it as a metaphor in his narration.

But more than that: one of the things that sets Teleny apart from 99% of erotic fiction for me is the visions that pepper the book, a blend of exoticism and sexuality that won’t seem alien to the Freudian proponents that will become so numerous in the following decades. Teleny might be pre-Freudian, but the strength and layers of meaning of its imagery obviously lent it to an adaptation as a comic. Jon Macy faithfully adapts these visions and adds his own, placing himself in the company of those anonymous men who collectively wrote Teleny.

As I said above, Jon Macy hasn’t tried to brush the more shocking aspects of the novel under the carpet. He didn’t cut a gory sequence involving two (female) whores, a scene that’s probably as grotesque as anything Sade has written2; nor did he shy away from the original ending. But then, he did something that some readers might object to, but that I find completely coherent with the original text: he added his own ending to the story (I want to stress that he did not replace the original one, which would have been another matter), one that is in keeping with the social mores of the times and thus doesn’t feel out of place at all. For me, that’s not hubris, that’s, again, putting oneself in good company: that of the group of the 19th-century writers who produced the Hirsch manuscript. After all, Teleny is a fantasy, and what good is a fantasy if it can’t be tweaked to suit the desires and needs of its audience?

I really like the idea of reclaiming 19th-century gay-themed works for a modern, gay audience, as Tom Bouden did a decade ago with Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest. The original works still exist to be read and enjoyed, while such an adaptation envisages what Wilde and others might have done had they been free to express themselves as gay men.

If I may be allowed to somewhat overdo my conclusion, I’d say that Teleny and Camille is a proof that there is an exception to every rule: while Wilde wrote that each man kills the thing he loves, Jon Macy has instead given new life to an old, beloved book that has a lot to offer to modern readers.

————————————–

UP. 10/09: The book is now available from Amazon.

Notes:

- This 250-page book is published by Northwest Press, and will be available from the publisher around the end of July, before being available in comics shops a few months later. ↩

- And a scene that makes us question the view of women prevalent in the novel. There’s a good collection of essays about Teleny here, as well as an excerpt from Macy’s book. ↩

Bluesky feed

Bluesky feed

Francois, the imagery, especially what Camille pictures in his soul during Teleny’s concert, really grabbed me as well. Very important point you make about reclaiming works. It’s nice to see the cover of Leyland’s adaptation, too.